Introduction

Aspergillosis is an economically important respiratory disease in poultry caused by a fungus belonging to the genus Aspergillus. Immune compromised birds or exposure to high number of spores contributes to this disease. The main predisposing factor for the development of the disease is stress. Bird mortality and carcass condemnation leads to major economic losses.

Etiology

The fungal species A. fumigatus is a prevalent cause of the illness. These organisms are common soil saprophytes that feed on organic matter in a warm (>25°C) and humid environment, as well as hatchery eggs that have been damaged. Acute and chronic forms of aspergillosis exist. Acute aspergillosis is a fungal infection that affects young birds and causes a high rate of morbidity and mortality. The chronic type is infrequent, causes less death, and primarily affects older birds, particularly those with weakened immune systems as a result of poor husbandry.

Epidemiology

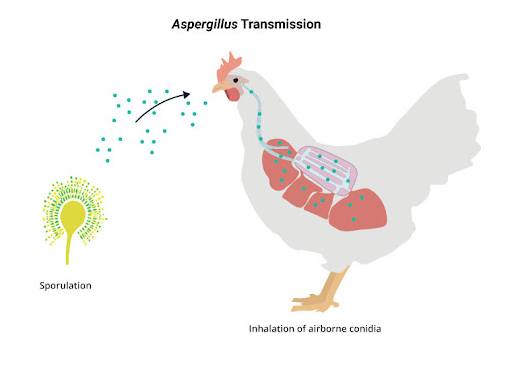

Aspergillus spp. are widely distributed, and the disease can be found wherever environmental conditions are appropriate for fungal growth. The disease is present throughout the year, although the percentage of positive isolates in both lung and environmental samples is higher in summer. Aspergillosis affects all birds. It has been found in both domestic and wild birds, including chickens, ducks, and quails. Conidia or spores inhaled through contaminated feed, faeces, soil, or contaminated eggs in-ovo infect the growing embryo.

In avian respiratory tract because of the reason that air (or conidia) reaches the caudal air sacs before passing through the parts of the lungs where gas exchange occurs, the small non-expanding lungs and nine air sacs serve as a main nidus for infection. Moreover, faster fungal growth is also possible with a higher body temperature. These factors make birds highly susceptible to infections.

Pathogenesis

Inhalation of large numbers of tiny, hydrophobic fungal spores into the respiratory system is responsible for entry of the fungus. After spores infect the tracheal, nasal, bronchial, and air sac epithelium, they penetrate the respiratory tissue and reproduce to create mycelia, which leads to the formation of granulomas. They are then hematogeneously distributed to other tissues such as the brain, pericardium, bone marrow, kidney, and other soft tissue. With heterophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and some large cells invading the lesion and producing lesion, tissue invasion causes an inflammatory response.

Clinical Signs

The number of spores that enter the body and the organ system that is involved determines the clinical signs, which can range from respiratory tract sickness to central nervous system disease. Diffuse lower respiratory tract illnesses, granuloma formation, and localised CNS graunuloma are three major presentations of the disease. Due to the initial closure of the air route, freshly hatched chicken show difficult breathing and start breathing with an open mouth (gaspers) within the first 3-5 days. The birds that survive may appear dull and stunted, exhibit lethargy, a lack of appetite, emaciation, increased thirst, develop eye edema or blindness, and exhibit torticollis.

Post mortem findings

The lungs and air sacs are the most common sites for lesions, but other organs may also be involved. White to yellowish granulomas ranging from pinhead or miller seed up to the size of a pea may be present. Serosa and parenchyma of the other organs involved may also have roughly spherical granulomatous nodules (>2 cm). Aspergillosis affecting the visceral organs, result in nodular granulomatous lesions.

Diagnosis

History, clinical presentation, postmortem findings, haematology, biochemistry, serology, radiographic abnormalities, endoscopy, and fungus culture are commonly used to make a diagnosis. Because clinical diagnosis of aspergillosis in birds is challenging, postmortem observations of white caseous nodules in the lungs or air sacs of infected birds are frequently used. On the serosa and parenchyma of respiratory tracts, granulomatous nodules and cheesy plaques are seen. However, conclusive diagnosis is dependent on the isolation of Aspergillus species or the presence of the fungus during a histological inspection.

Preparation of a wet smear can also be used to identification. A nodule can be dissected and crushed on a slide beneath a cover slip in a drop of 20 percent potassium hydroxide and lactophenol cotton blue. The fungal hyphae are stained with lactophenol cotton blue.

Tissue samples are fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed, and embedded in paraffin blocks, then stained using the haematoxylin and eosin (HE) procedure.

The pathogenic organism must be isolated by growing it on differential medium for accurate species identification. Small sections of lesions are aseptically removed and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C on plates or slants with malt agar, Sabouraud’s glucose agar, or antibiotics. The characteristic conidial head and colony of Aspergillus species can be identified.

Differential diagnosis

It includes infectious bronchitis, newcastle disease, infectious larngeo tracheaties, dactylaria infection and nutritional encephalomalacia.

Treatment

No effective treatment for Aspergillosis. The administration of one or more systemic antifungal agents is used to treat aspergillosis. Itraconazole, ketoconazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, fluconazole, and Amphotercin B are some of the most often used drugs. Itraconazole is choice of drug for this disease.

Reduced exposure to the fungus and associated risk factors are essential for management. Hatchery sanitation has helped to control Aspergillus fumigatus in young chickens. To minimize the outbreak of aspergillosis, avoid using mouldy litter or feed. Antifungal substances should be used to treat the poultry coop and litter.

Dr. Asiya Mushtaq, Dr. Sundus Gazal